Days one through seventy are the most critical period for developing your future cow. What are you doing to set your newborns up for success?

It seems every discussion surrounding calf raising includes colostrum – that key first nutrient and antibody packed meal, critical to helping protect the newborn for the first weeks of life, until their own immune system can produce protective antibodies. Calves are born without any immunity because antibody proteins are not able to pass through the placental barrier. There are several factors impacting how much immunity a calf gains from the colostrum it is fed. But colostrum also does much more than immunity for the newborn, including things as simple as the delivery of colostrum at an appropriate temperature being important to warming of the calf. Colostrum has been found to contain over 200 bioactive compounds (Blum and Baumrucker 2000) which also affect overall absorption of nutrients, growth, and future milk production (VanAmburgh and Soberon 2016).

Quality & Quantity.The goal should always be the delivery of four quarts of high-quality colostrum into the calf within the first hour after birth. This is because the calf’s ability to absorb antibodies is decreased by 25% already, just four hours after birth and virtually gone by 24 hours of age (Stott et al. 1979). There can be drastic variability among cows regarding the concentration of IgG in their colostrum and an IgG level equal to or exceeding 50 g IgG per liter is the highest quality. This can easily be tested using a Brix refractometer, where a reading of greater than 22% would be the cut off for colostrum measuring above the desired 50g IgG/L. To achieve a good level of immunity, the calf must consume more than 200 grams of immunoglobulin IgG, hence delivering four quarts.

There are several factors that influence colostrum quality, including the dry cow ration and vaccination program. Avoiding short dry periods of less than 30 days, overcrowding or heat stress for dry cows also affects quality, along with getting the fresh cow milked within 1-2 hours after calving. Colostrum quality decreases 3% for every hour of delayed milking. For example, if the cow calves at 6p.m. and isn’t milked until 6 a.m., her colostrum concentration is lowered by 36% because her body is already beginning to make milk (Dumm).

Colostrum should be delivered to the calf at temperature of 95-105oF (32-43oC). Absorption will be poor if it is delivered too cool and above 110oF there is risk of causing burns or irritation to the esophagus and digestive tract. A rule of thumb presented by Dr. Rick Dumm, DVM at the recent World Dairy Expo was to feed 10% of the calf’s body weight in high-quality colostrum at the first feeding, then eight hours later feed another 5% of the calf’s body weight in an effort to consistently achieve desired serum IgG levels.

Good stuff. Immunoglobulins are a common part of any colostrum discussion, but what do we know about them? The normal distribution of immunoglobulins in colostrum is 5% IgA, 7% IgM, and 85-90% IgG. All of these Ig types function together, but IgG is the primary contributor to systemic immunity and also functions within the intestine, where IgM has a major role in preventing septicemia and immunity to enteric pathogens. IgA has a lesser role in intestinal immunity to enteric pathogens, but is still a vital part of the immunoglobulin team (Davis and Drackley 1998).

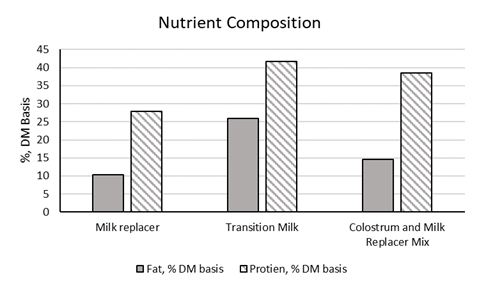

Colostrum has about twice the level of solids and energy of normal milk, providing the newborn with double the nutrition of regular milk and the IgG found in colostrum are virtually non-existent in regular milk. The same is true for the antibacterial Lactoferrin, which is also present in colostrum at a fairly high level and virtually undetectable in regular milk (Kertz).

Keep It Clean. Absorption can be reduced by stress, including difficult calving, heat, or rough handling or feeding of calves, but another serious source is bacterial contamination of colostrum. There have been several studies that showed colostrum samples exceeding upper limits of 100,000 cfu/ml for total bacteria and 10,000 cfu/ml for coliform (Kertz).

Primary sources of this bacterial contamination have been found to be dirty udders, bacterial proliferation after improper storage, and dirty equipment used to milk, transfer and feed the calf (Godden 2007). Items to keep in mind as critical to reducing opportunities for contamination related to the cow are proper udder prep for milking and not letting calves suckle their dam. Colostrum should not be pooled unless it will be pasteurized prior to feeding. If colostrum will be stored, refrigerate it in a manner that it can cool within one hour to the refrigerator temperature, and don’t store it more than 48 hours in a refrigerator. Colostrum may also be frozen. Whatever the method you choose, be sure to label the colostrum prior to storage with the date harvested and Brix refractometer test reading for quality.

Always wear gloves or have very clean hands when feeding newborns. Whether you choose to let the calf suckle a bottle or use an esophageal feeder is your choice, just get the volume in and be sure all milking and feeding equipment is clean. If your bottles, nipples or tube feeders are in need of replacement, visit calf-tel.com or your local dealer to be sure your equipment is in top condition to care for newborn calves. Here is a study that compared bottle and tube feeding results.

Pasteurization of colostrum can reduce pathogens in colostrum, but it is done differently because the density of nutrients is different from whole milk. The fat content of colostrum can be double that of whole milk, while the protein content can be 4x higher. Therefore, the best results are achieved when pasteurizing at 140oF for 60 minutes. If colostrum were to be pasteurized at too high of a temperature the resulting thick liquid is very hard to feed or clean off equipment. Cleaning protocols are discussed in detail in our blog article titled: “When it comes to calves—keep it clean!” here in Calf-Tel’s Calf Corner. However, if you are checking cleanliness with an ATP meter, the goal for all milk contact surfaces should be under 100 and a score under 10 is excellent.

Kelly Driver has been involved in the New York dairy industry all her life. In addition to raising dairy calves and replacement heifers, she is the Northeast Territory Manager for Calf-Tel. Feel free to contact her at kellydriver@hampelcorp.com with your calf questions or suggest a topic you would like covered in a future blog.

Sources

- Blum, J.W. and C.R. Baumrucker. 2002. Colostrum and milk insulin-like growth factors and related substances: mammary gland and neonatal (intestinal and systemic) targets. Dom. Anim. Endo. 23:101-110.

- Davis, C.L. and J.K. Drackley. 1998. The Development, Nutrition, and Management of the Young Calf. Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA. p. 179-206.

- Godden, S. 2018. Advances in colostrum management. Proc. Dairy Calf and Heifer Assoc., Milwaukee, WI, p.40-50.

- Dumm, R. 2019, October 2. Colostrum for many other reasons. Presented at World Dairy Expo, Madison, WI.

- Kertz, A.F. 2019. Dairy Calf and Heifer Feeding and Management: Some Key Concepts and Practices. Outskirts Press, Denver, CO. p. 8-15.

- Van Amburgh, M.E. and F. Soberon. 2016. Developing a quality heifer: management, economic and biological factors to consider. Proc. Dairy Calf and Heifer Assoc., Madison, WI, p.37-44.