By Grace Kline

My husband and I recently reorganized our calf housing on our dairy farm. We covered a section of lawn with gravel, and added stone dust on top of the gravel to make a flat and even surface that allows moisture to pass through. We have 15 individual hutches, and 4 super hutches for the weaned calves. Shortly after finishing this project, my grandparents came to visit, which always includes a walk around the farm. My grandparents owned and milked cows several years ago. That experience gives them a deep appreciation for what we do, and for the changes and advancements the industry has made over the years.

After seeing our hutch area, my grandmother made a comment along the lines of; “Wow. I wish I had something like this when I raised calves. We used to tie them up in front of the cows next to the feed troughs!” Even 10 years ago, I saw an example of this myself when walking a tie stall barn that had already filled their hutches and had extra calves.

This comment had me thinking about how different calf care ideas and protocols had been put in place. While there are different ways of doing them, the basics come down to colostrum within the first hour, dip the navel, and house in a clean environment. Today, we know how important it is to do each of these things. But, I want to review a study from 1986 that was published in The Journal of Dairy Science by William J. Goodger and Eileen M Theodore. This is a study that was done 37 years ago, which “examined 10 separate management areas with a total of 83 potential management decisions to provide a more comprehensive view of management practices.” I would like to compare the dairy manager’s answers to the interview questions and the observations of those conducting the study to what we consider the standard today.

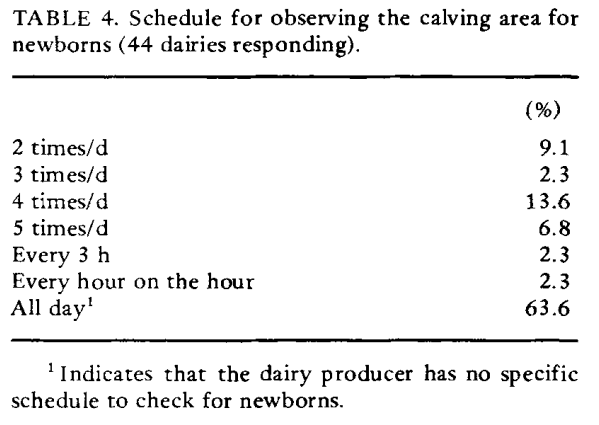

We know that it is important to feed colostrum within the first hour of birth as that is when the calf can achieve the highest IgG (immunoglobin G) absorption. Considering that fact, it is also important to check the calving areas regularly to identify cows in labor and be prepared to take care of the newborn. Today, dairies can use activity monitors and cameras if the manager cannot be physically present to check the calving areas as often as they see fit. During this study, it was found that the majority of managers did not have a schedule to check the calving areas, which can result in many different calving/newborn issues.

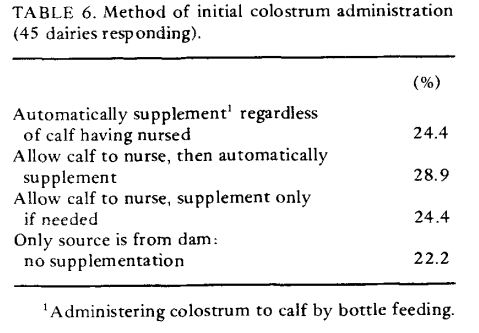

When it comes to actually feeding the colostrum, there are 3 different ways to complete this task that come to mind. It can be fed by a bottle, an esophageal tube feeder, or by the cow herself. Opinions differ on which is the best option. Feeding by a bottle allows the calf to nurse the way it naturally would, however the calf may not drink the entire gallon that is recommended. Feeding by an esophageal tube feeder ensures the calf takes the entire amount of colostrum, but the user runs the risk of drowning the calf if it is not done properly. A calf may nurse off the cow if the calf has not yet been seen and removed from the cow. Calves can struggle to stand within the first hour of birth without assistance and will not be able to reach the udder. Some cows do not allow the calves to suck and may injure them by kicking or trying to get away from the calf. If a cow does allow the calf to suck, the teat may not be properly cleaned which could introduce unwanted bacteria to the calf. The calf’s teeth may also damage the cow’s teat, making milking difficult and/or painful.

When we look back to 37 years ago, allowing the calf to nurse was a common practice among farmers. While the answers were pretty close across the board, the most popular answer was to allow the calf to nurse first, then step in and supplement to be sure the calf received the full amount. For hygiene and efficiency reasons, calves should receive colostrum from a bottle or esophageal tube feeder. Immunoglobulin absorption recommendations were not listed in this study, and IgG levels were not checked or reported on these dairies for the purpose of the study. However, one paragraph that I found interesting stated that it was common practice to discard the colostrum from first lactation animals and only use colostrum from 2nd lactation and higher cows (pg. 4). The reasoning behind that was that those animals would contribute higher antibody levels. Now, testing colostrum with a colostometer or a brix refractometer, we know that colostrum at 50 mg/mL of Ig is considered quality colostrum (Ishler, Schurman; 2023). This translates to a reading of 22% or higher on a brix refractometer, or the green section of the colostrumeter tool. Testing colostrum allows us to only discard the inadequate colostrum, instead of basing the quality on lactation number or age of the cow.

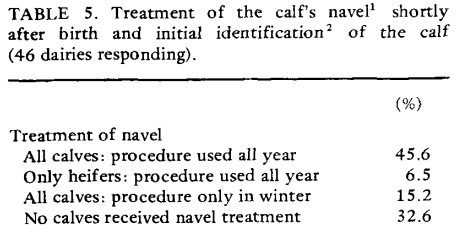

When the calf is born, the exposed naval can act as a pathway for bacteria to reach the calf’s body. An infected naval will become swollen, and if not treated in time, begin to cause joint illness and swelling in the knees. To prevent the navel infections, dipping in a 7% iodine (Godkin, 2019) helps clean and dry out the navel. This should be done for all calves, as bacteria can be picked up just about anywhere. Dipping the navel is a widely used protocol, however, it did not used to be for all dairies. The study showed that over half of the participating dairies were selective when it came to dipping navels.

Calf housing can be a hefty discussion. It is done in a few different ways, with new ideas and studies coming all the time. My personal preference is individual housing in a calf hutch. I chose this as I prefer my calves separated to minimize the spread of disease, and I can see each calf’s individual development. I also find that the calves are comfortable in hutches that have superior ventilation such as Calf-Tel strives for. However, as I said before, I only have 15 hutches. Larger dairies have been making use of calf barns, which allows you to reduce labor when you have more calves. During this study, it was found that 76% of dairies had their calves in group pens while 24% of dairies used individual housing. At the time of this study, individual calf housing was being pushed as the most effective way to raise calves to prevent disease. It was stated that the most common individual housing was constructed of wood, which can hold onto bacteria and moisture. Today, the use of plastics has allowed farmers to keep a cleaner living area for their calves, but the housing situations still differ. Calf barns can contain both individual and group housing, and new studies show that some calves perform better when paired with a partner. That idea encouraged the paired housing units now sold by Calf-Tel. When deciding what housing design is right for your dairy, it may be helpful to visit other farms (with the owners permission) and ask the manager why they decided on their design. You will be able to compare their thoughts to your needs and see what is right for you.

As you can see, we have come a long way in a relatively short period of time. The advancements in technology and new ideas have allowed us to discover new and more efficient methods of calf raising, which will only improve with time.

Raised on a dairy farm, Grace Kline now manages the calves and heifers at Diamond Valley Dairy, owned by her husband, Jacob Kline, and two brothers-in-law, Josh and Jesse Kline. They milk 60 cows in Southeast Pennsylvania and raising their calves and calves born of embryo transfers from brood cows that have competed well in the show ring.

Ishler, V., & Schurman, E. (2023, January 4). Colostrum management tools: Hydrometers and refractometers. Penn State Extension. Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://extension.psu.edu/colostrum-management-tools-hydrometers-and-refractometers#:~:text=A%20Brix%20value%20of%2022,be%20considered%20high%20quality%20colostrum.

Godkin, A. (2019, August 1). Preventing navel infections in newborn calves. CalfCare.ca. Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://calfcare.ca/management/first-24-hours/navel-care/preventing-navel-infections-in-newborn-calves/

Goodger, W. J., & Theodore, E. M. (1986). Calf Management Practices and Health Management Decisions on Large Dairies. Journal of Dairy Science, 69(2). https://doi.org/https://www.journalofdairyscience.org/article/S0022-0302(86)80442-8/pdf