Exploring options and regulations in the United States, Canada, and Europe

by Grace Kline

To ensure proper animal husbandry, guidelines have been established to create a uniform standard of care within each respective country or union. Those guidelines will be reviewed below, along with links to various informative websites if you wish to continue your research.

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, I’m here to remind you once again that calf care is an extremely important aspect of your dairy. The calves are the next generation of your herd. The quality of care (or lack thereof) determines their performance in your milking herd. So, if you want healthy cows that milk well and breed back year after year, you must start by keeping your young herd healthy.

United States

Every 3 years in the United States, the FARM (Farmers Assuring Responsible Management) Program is updated. Due to the Coronavirus Pandemic in 2020, the update was extended. Now, all updates will be put into effect on July 1st instead of January 1st. Version 5 will go into effect on July 1st, 2024.

Before we get into the updates, FARM has released an Evaluation Prep Guide to help farmers understand what changes they will need to make. Please check out the link so you can best prepare for any evaluations you may have if you are a part of the FARM program.

There are not many updates from Version 4 of the FARM program to Version 5. Here are the few to note:

- In addition to a minimum of 95% of your herd scoring below a 2 on the locomotion score card provided by FARM, a minimum of 85% of your herd must score 1 or less. This applies to your lactating herd. Locomotion score cards are used to monitor any lameness or difficulty walking within your herd.

- Pain mitigation for disbudding has been discussed in a previous Calf-Tel blog, which you can find here. It is not something we should ignore, as disbudding is a very stressful event. Version 5 has upgraded their improvement opportunity from a continuous action plan to a mandatory improvement plan. This means that you will not have up to 3 years to complete this change, but only 9 months. If you’re not sure what steps to take, consult your veterinarian. In Version 4, the method in which disbudding takes place was not specified, however in Version 5 it is recommended that farmers use a paste or a butane burner.

- Even if calves are not staying on the farm, FARM advises feeding high quality colostrum to all calves in a timely fashion. The updated version states that a colostrumeter or any other form of colostrum quality measurement can be used, and the amount should be at least 10% of the calf’s bodyweight. It can be demonstrated by record keeping or keeping evidence of bloodwork done to ensure the calf maintained a successful transfer of passive immunity.

- Both euthanasia and job specific continuing education have been upgraded from a continuous action plan to a mandatory action plan, meaning that you have only 9 months to demonstrate that these protocols have been implemented on your farm. To complete euthanasia, you must have 2 individuals and provide a method and confirmation of death. This can mean that you and another employee put down a calf and agree that the animal is dead by listening for a heartbeat.

Farms that are members or ship milk to any organization that has signed a FARM Animal Care Participation Agreement will be subject to evaluations and any second- or third-party evaluations to remain sure the guidelines are being followed.

Canada

In 2023, the Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Dairy Cattle was released. To view the publication, visit the National Farm Animals Care Council website and select your viewing preference. This Code of Practice serves as Canada’s rules and guidelines for farm animal care.

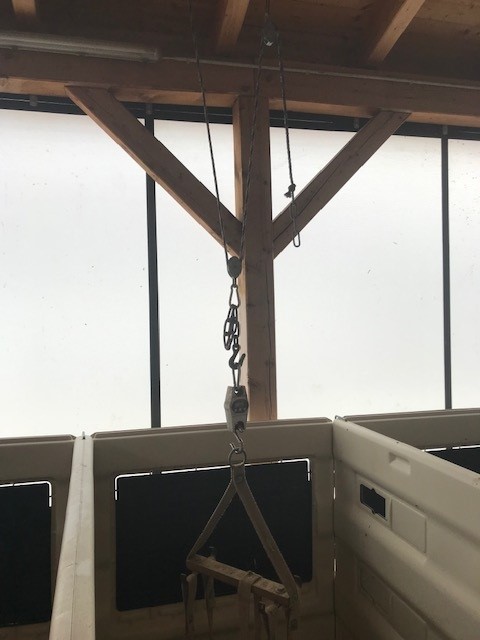

New research has been conducted showing the benefits of paired calf housing. Paired calf housing can help to reduce stress in calves and increase starter intake. You can read interviews from farmers using paired calf housing in another Calf-Tel blog, “Are Calves Better Together?” Because of this research, Calf-Tel has begun manufacturing products that make it easier for farmers to pair calves together in a way that is both sanitary and efficient. To view paired calf housing options, visit Calf-Tel’s website under the Social Calf Housing tab.

Requirements for calf housing in Canada include having proper space for each calf to stand up and lie down comfortably, reducing instances of tethering, and allowing calves to have social contact. Calves being housed inside are no longer able to be tethered. Calves being housed outside can be tethered specifically with a collar, only if the tether allows the calf to walk outside their hutch and socialize with other calves. Calves being housed outdoors must be able to have physical contact with other calves. By April 2031, calves being housed indoors must be in social housing as part of a new regulation. By 4 weeks of age, healthy calves should be housed together.

As a general rule of thumb, I keep my own calves at 12%-13% solids in the summer and 14% solids in the winter to help with cold stress. This is what works in our herd with our milk replacer. To find what will work best for you, consult a calf nutritionist familiar with your milk replacer, and even your veterinarian. Check out this Calf-Tel blog, “Milk Replacer Management” to help prepare you for those conversations. Providing adequate water at these percentages is essential for proper digestion. Canadian regulations require that newborn calves be offered at least 15% of their birth weight up to a week old, around 6 liters for Holsteins. At 7-28 days, calves should be given 20% of their birth weight, around 8 liters for Holstiens. From then on, calves should be offered up to 10 liters to promote high daily gains, aiming for 2.2 pounds per day.

A proper veterinary client patient relationship is crucial for herd health on your dairy. Your relationship with your vet will help you make transitions in calf housing, make sure your calves are getting enough nutrition, and properly diagnose illnesses. For assistance in diagnosing a suspected illness on farm, you can view this Calf Health Scoring Chart.

Europe

Care4Dairy lists European best practices in multiple categories in easy-to-read formats. We will also refer to Council Directive 2008/119/EC. Under calf nutrition, we see that if a calf is not able to nurse of their mother or a foster cow, it is recommended that milk or milk replacer is fed a minimum of 4 times a day, the maximum time between feeding being 8 hours. Calves are also weaned much later, at 12-17 weeks rather than 8 weeks. This is to help reduce stress during weaning and reduce instances of post weaning weight loss. Calves should be exposed to water or electrolytes at all times after the age of 2 weeks to encourage proper digestion of the feed.

Calves should be housed in groups, to allow for social interaction and exercise. If calves are to be kept individually, they should be able to see other calves and have tactile contact unless they are being separated for medical reasons. Calf housing materials should not be porous, and allow for easily cleaning and disinfecting. Tethering is not permitted in either indoor or outdoor housing. Calves also must be inspected at least twice a day to check for any illness or injury that may occur.

All calves should have enough room to stand, turn around, lie down, and groom themselves as this is normal calf behavior. In addition to this, the flooring and bedding in those housing areas should be clean and dry with enough traction to prevent any falls or slips. Proper cleaning of housing areas can be achieved by frequent washing, and the use of non-porous material. If housed indoors, ensuring calves have adequate time with the lights both on and off will encourage both eating and resting behaviors.

Standards and animal care practices vary from country to country. As long as the animals are well fed, growing and producing, different does not mean wrong. Check out the links within this blog to read more in depth about farm animal care in other parts of the world!

About the Author

Grace Kline works with her husband Jacob alongside brothers-in-law Josh and Jesse. Together, they operate Diamond Valley Dairy in Southeastern Pennsylvania. Diamond Valley is a 60-cow operation, where Grace works full time as the calf and heifer manager among many other tasks. Graduating from Morrisville State College in 2022, Grace received her Bachelor’s in Business Development and completed an internship in Wisconsin in 2021 where she spent time learning the calf operation at Budjon Farms.