Alycia Drwencke, Sarah Adcock, Cassandra Tucker

In the U.S., 94% of farms disbud their dairy calves. Despite how common it is, the number of decisions involved with disbudding are not often discussed. We have laid out several areas for considerations with this procedure, based on research we have conducted in recent years.

One of the first decisions is which tool to use for disbudding. Currently, the two most common methods use a hot iron or caustic paste. We have used both methods in our research and discuss the timing and some techniques that are used.

Hot iron disbudding

Tools: Several disbudding irons are available, and they use either butane or electricity for heat. Having an outlet near the calves makes the electric option a good choice, and butane power often makes more sense in outdoor housing or in barns where electricity is not nearby. Sometimes the size of the iron tips varies, for example, ¼ or ½ inch. We use the ¼ inch tip with young calves, 2 weeks or less, and the ½ inch tip when we disbud calves between 3 to 8 weeks of age. We adjust the tip size with age to create the smallest wound possible while making a uniform copper ring around the base of the bud.

Timing: Disbudding before 8 weeks of age reduces the need for more invasive procedures. The best time to use an iron in the first 8 weeks is still unclear. Disbudding at a younger age may lead to more sensitivity to other procedures later in life (Adcock and Tucker, 2020). Near 8 weeks there may be a greater risk for scurs as the horn buds are bigger and disbudding is more likely to overlap with other stressful events such as weaning. We typically disbud before 6 weeks to minimize the overlap with weaning and large horn buds.

Techniques: Beyond the decision to use a butane or electric iron, considerations for hot iron disbudding include shaving the hair or not, the temperature of the iron, the amount of time the iron will be applied, motion of the iron and whether the horn bud will be left in or scooped out to remove it. When disbudding, we have the best success when our iron is heated to between 750 to 900°F. The iron can cool down as we disbud calf after calf and so we re-check the temperature with an infrared gun when doing multiple disbuddings (Figure 1).We apply the hot iron to a shaved horn bud with a small amount of pressure while gently rocking around the base of the horn bud for 10 to 20 seconds until a uniform cooper ring is formed and leave the bud in. For some irons, like the butane Portosol it is also important to consider the depth in which the iron will be applied, as these irons can easily “cut” into the calf’s head, creating a deeper wound. To minimize the wound size and damage, we only burn the horn growing tissue around the bud, highlighting the importance of watching the depth of the iron and avoiding burning into the white fat tissue.

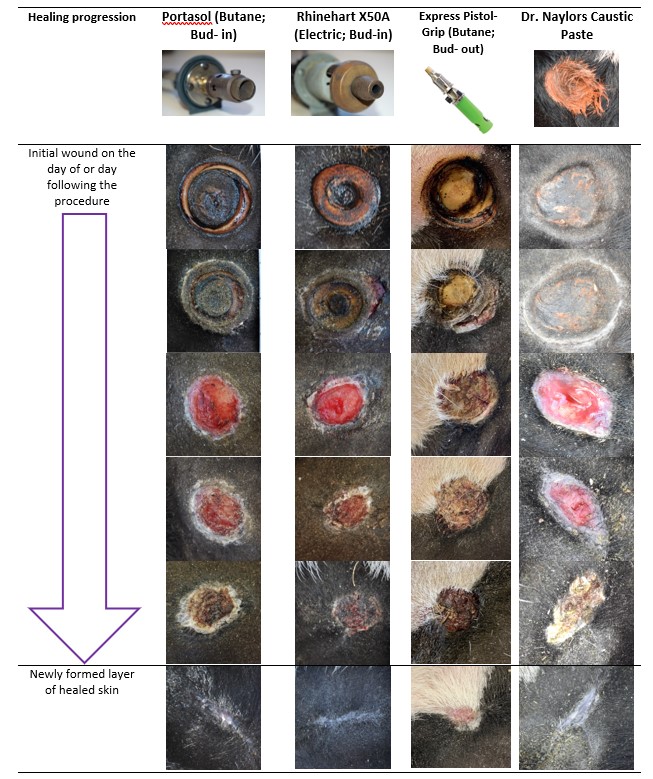

Outcomes from our research: In a study comparing an electric and butane hot iron, wounds for both types of iron went through similar stages and were healed in ~8 weeks (Figure 2; Adcock et al., 2019). Throughout this healing time, calves disbudded with a hot iron show increased sensitivity to touch compared to intact horn buds for at least 3 weeks and fully healed tissue (Adcock and Tucker, 2018). In a recent study, our collaborators Reedman et al. (2022), used the bud-out approach and found that approximately 50% of calves had healed wounds at 7 weeks, suggesting a similar healing timeline to the bud in method. There is currently no published data looking at how leaving the bud in or taking it out may affect the calves.

Caustic Paste Disbudding

Tools: Currently there are several types of paste available including Dr. Naylor’s, Remoov, Hornex, etc. No detailed comparisons have been made between these brands. In our work we have primarily used Dr. Naylor’s but also used Hornex, a paste common in New Zealand, in a pilot study.

Timing: Typically, paste is applied within the first week of life because this is when the horn bud is small enough to be destroyed by a small amount of paste. Calves that are only a few days old also move less than older ones. This may favor earlier application because, one challenge with paste is how easily it can rub off from the horn bud onto other parts of the calf, housing, and pen mates. An unwanted burn will result on any body part it contacts. If paste is found in an undesired area, we used vinegar to neutralize the paste and stop it from creating any further burns.

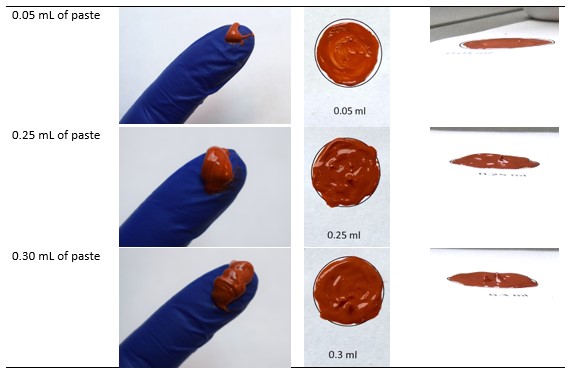

Techniques: For caustic paste, technique decisions include the amount of paste, use of a balm around the horn bud, covering with tape, shaving the hair, or wiping the paste off after a set time period. The suggested amount of paste to use varies by manufacturer by referring to a quarter, a pea, or the amount of turns in the tube you should make. In our recent study (Drwencke et al.) we applied Dr. Naylor’s paste on the third day of life using 0.25 mL per unshaved horn bud on calves weighing less than 75 lbs and 0.3 mL for those 75 lb or more (Figure 3). These amounts allowed for sufficient coverage of the horn bud when applied and resulted in no regrowth. In a pilot study, we used only 0.05 mL per horn bud, but this amount did not lead to sufficient damage to horn-growing tissue and lead to regrowth in 46% of animals. While the precise quantity to apply is still unknown, one thing is clear, a large volume of paste leads to extreme burns. When too much is applied, the paste wounds increase in size and severity, often creating a wound that looks like a plate on the top of the head instead of being focused on the horn bud (Figure 4). In addition to preventing more severe injuries, using less paste may reduce the risk of undesired burns.

In a pilot test, we found that using a balm increased the paste running and mixed with it, creating a mess. When tape was used, we found the paste spread out more and increased the size of the wounds. Farms have reported mixed results with how successful they found the use of tape and balms (Saraceni et al., 2021). In our recent study (2021), we chose to leave the horn buds unshaved, based on a producer recommendation who was having success with it keeping the paste where it was applied. Other producers have also mentioned wiping the paste off after an hour of application to help reduce the risk of calves rubbing it off. There is currently no research available on how shaving the hair, using tape or balm, or wiping paste off may influence disbudding success, infection rates, wound severity, or other factors.

Outcomes from our research: We found that caustic paste wounds took an average of 15 weeks to heal, twice as long as hot iron wounds. While the wounds followed a similar progression, the paste wounds sank into the calf’s head, which differed from the hot iron wounds (Figure 2). The wounds from caustic paste disbudding are also more sensitive to touch for at least 6 weeks compared to intact buds, which is as long as we looked before disbudding the control calves. We also found that calves with caustic paste wounds were more responsive to touch on their wounds through the entire process than healed tissue.

Best practice for mitigating pain

Regardless of the method or timing of disbudding, the current gold standard for mitigating pain is to combine a local block and an NSAID (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug). A local block, such as lidocaine, reduces the initial pain at the time of the procedure, both for hot iron and caustic paste disbudding. Behavioral changes that indicate pain are observed immediately for hot iron disbudding and within 5 minutes of paste being applied, supporting the use of a local block. An NSAID like meloxicam helps suppress the inflammatory response for up to 3 days afterwards. Pairing a local block with an NSAID is the best currently available technique for pain relief. We have made a YouTube video that shows how we give pain relief and hot iron disbud. An additional resource is available by visiting this website from the University of Guelph.

Other considerations

Two other considerations for farms as they approach disbudding include the risk of horn regrowth and the ease of implementation. Horns can regrow with any method of disbudding if there is insufficient tissue damage. Some farms have reported a higher rate of horn regrowth when using caustic paste compared to hot iron (Saraceni et al., 2021). Finally, the ease of implementation either due to employee training, access to resources such as electricity, and cooperative standards can all influence the method and technique of disbudding on farm.

Figure 1: An infrared sensor is used to measure the temperature of a hot iron. When disbudding, hot irons should be heated to between 750°F to 900°F. The iron can cool as it is used on calves and should be re-checked for temperature when disbudding a series of calves, one after another.

Figure 2: The wound healing process following disbudding with 3 different tools. The final photo shows when a new layer of skin has formed. For hot iron disbudding this takes an average of 8 weeks and caustic paste average 15 weeks.

Figure 3: Paste on a gloved finger and spread in the area of a US quarter. Our research used 0.25 mL on calves weighing less than 75 lbs and 0.3 mL on calves’ weighing 75 lbs or more. In a pilot study, 0.05 mL resulted in almost half the calves re-growing horns, while the 0.25-0.30 mL prevented all horn regrowth.

Figure 4: A large disbudding wound from applying too much paste. The approximate size of the horn bud is indicated by the white circle. The wound extends far beyond the edges of the horn bud, indicating less paste could have been used and created a smaller wound.

References:

Adcock, S. J., & Tucker, C. B. (2018). The effect of disbudding age on healing and pain sensitivity in dairy calves. Journal of Dairy Science, 101(11), 10361-10373. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-14987

Adcock, S. J., & Tucker, C. B. (2020). The effect of early burn injury on sensitivity to future painful stimuli in dairy heifers. Plos one, 15(6), e0233711. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233711

Adcock, S. J., Vieira, S. K., Alvarez, L., & Tucker, C. B. (2019). Iron and laterality effects on healing of cautery disbudding wounds in dairy calves. Journal of Dairy Science, 102(11), 10163-10172. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-16121

Drwencke, A.M., Adcock, S.J.J., Tucker, C.B. Wound healing and pain sensitivity following caustic paste disbudding in dairy calves. In preparation.

Reedman, C. N., Duffield, T. F., DeVries, T. J., Lissemore, K. D., Adcock, S. J., Tucker, C. B., Parsons, S.D., & Winder, C. B. (2022). Effect of plane of nutrition and analgesic drug treatment on wound healing and pain following cautery disbudding in preweaning dairy calves. Journal of Dairy Science, 105(7), 6220-6239. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-21552

Saraceni, J., Winder, C. B., Renaud, D. L., Miltenburg, C., Nelson, E., & Van Os, J. M. (2021). Disbudding and dehorning practices for preweaned dairy calves by farmers in Wisconsin, USA. Journal of Dairy Science, 104(11), 11995-12008. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-20411