by Kelly Driver

As labor costs continue to rise, many calf raisers are looking for every bit of increased efficiency they can add to their operations, while still maintaining top level care for the calves. Let’s take a look at some of the areas different producers have focused on in the quest for greater efficiency.

Feeding milk. The most important and time-consuming task in calf raising is feeding, whether it is milk, water or calf starter. And so, it naturally becomes one of the first places we look to gain efficiency. For smaller operations, it may mean an investment in a motorized device with a tank to deliver milk or water without carrying countless pails from the milk room to each calf individually. For larger operations hutch operations, a bottle trailer to fill, deliver and even wash the bottles may fill the need to feed more calves in timely fashion.

Portable milk pasteurizers offer efficiency when feeding a smaller number of calves. These units are versatile enough to batch pasteurize whole milk and the unit can then be wheeled to the calf housing area to dispense the milk. These units can also be used to reliably mix milk replacer for delivery as well. One farm I work with regularly found the time spent at each feeding reduced from 2.5 hours to 20 minutes when they converted to a portable pasteurizer rather than multiple trips carrying pails of milk to their calf area.

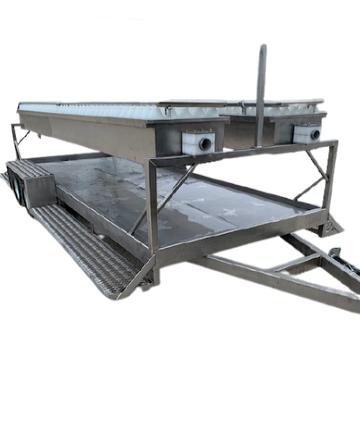

When feeding hundreds or thousands of calves’, bottle trailers, like the one at left available from Calf-Star, are available in different sizes that can make feeding milk much more efficient. These stainless-steel trailers have bottle compartments where calf raisers can fill the bottles and feed by standing on the trailer side platform. To see this trailer in use, click here.

Once feeding is complete, the trailer returns to the milk kitchen area and the bottle compartments can be flipped upside down to wash, eliminating the time to hand washing bottles.

Grain cart. Prior to re-purposing this gravity wagon into a grain cart, calf starter grains were being delivered to the 450-hutch calf nursery in bags at Lamb Farms, Inc. in New York. “The cost difference between bagged and bulk feed alone paid for this in just four months,” notes Kendra Lamb. “That doesn’t even factor in the labor savings of being able to drive through the hutch area and just fill buckets to feed.”

Bedding hutches. It is no secret that adding straw to hutches demands time and labor, often several times each week in colder climates. One of the most common discussions I have on farm visits is how to make bedding hutches less labor intense. For Probst Feedlot LLC, a 725-hutch calf nursery in central Illinois, the decision to purchase a Teagle bale processor was easy. The bedding chopper holds two 4-foot square bales at a time, allowing Probst’s team to bed 100 hutches every 20 minutes. The Probst team figures the equipment purchase of both a used tractor and the bale shredder paid for itself in less than a year, as bedding by hand would require another full-time employee on the team. With the use of the bale processor, bedding costs per calf are 17 cents per day, including labor, at the calf nursery. To see the system, visit https://www.teaglemachinery.com/en-US/Products/Bale-Processors/Telehawk.

Washing hutches. It is sometimes surprising how many farms I visit are still moving hutches one at a time to the area where they are pressure washed and cleaned. And it is especially surprising that as herds grow, this practice gets overlooked in the quest for more efficiency.

Imagine how much time would be saved if a simple attachment to the front of a tractor or skidsteer moved 4-6 hutches at a time to the wash area? Two different producers in the Northeastern U.S. have created hutch movers that pick the hutches off the ground, carry them and hold while they are pressure washed and then return the hutches to a clean location, setting them neatly in a row. If this seems like something that only happens in a calf caregiver’s dream, take a look at the images below. Both are designed to quickly attach to the front of equipment likely already in use at the calf nursery each day.

Washing pens. Similar to some of the innovative hutch movers we have seen, here are some pen wash racks that producers have created that can also be easily picked up and moved with a tractor to clean pen pieces more efficiently.

The dictionary defines efficiency as “the (often measurable) ability to avoid wasting materials, energy, efforts, money, and time in doing something or in producing a desired result.” In calf raising that may mean the ability to do our work of raising healthy animals well and without waste of feed, labor, or time. In farming, efficiency also equates to real labor and cost savings for the operation.

Kelly Driver, MBA has been involved in the New York dairy industry all her life. She is the Eastern US & Canada Territory Manager for Calf-Tel. Feel free to contact her at kellydriver@hampelcorp.com with your calf questions or suggest a topic you would like addressed in a future blog.

Courtesy of our dealer –

CRI REPRODUCCIÓN ANIMAL

MÉXICO SA DE CV