Benefits of pair or group housing of calves and practical solutions for hutches

Jennifer Van Os, Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist in Animal Welfare

Rekia Salter, Masters student in Dairy Science

Kim Reuscher, PhD student in Dairy Science

Department of Animal and Dairy Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison

When it comes to raising dairy calves, two – or more – heads are better than one in several ways. For the past decades, the majority of calves in the U.S. and Canada are housed singly before weaning. In recent years, however, an increasing number of producers have been successfully raising dairy calves in pairs or groups.

The consensus from the research is now that pairs and small groups, when managed well, can provide clear benefits. Housing milk-fed calves with at least one social partner can result in triple-wins for animal welfare, calf growth performance, and consumer perception – all of which are important for the vitality and sustainability of the dairy industry.

Benefits for the calf. Having companionship is important for calves since dairy cattle are a social species. Calves learn to play well with others of their kind, both literally and figuratively. It’s important to maintain per-calf space allowance, meaning an increase in total space for pairs or groups. This larger space allows calves to show a wider range of natural behaviors, including playing. Having social contact early in life helps them learn appropriate social interactions and also improves their other learning abilities. Calves raised in social groups show flexibility and adaptability to change, including a better willingness to try new feeds such as hay and TMR. This translates into improved resilience to stress and less bellowing during weaning. When regrouped after weaning, they start feeding sooner and don’t show the same growth check that individually raised calves commonly do.

Benefits for growth performance.Across a dozen studies, calves raised in pairs or small groups have outperformed single calves in one or more ways. Performance advantages were especially apparent for calves fed higher milk or replacer allowances (such as 8 quarts/day or more at the peak).

- Solid feed intake: by 1/4 to 1 pound per day pre-weaning and 3/4 to 2.5 pounds per day post-weaning

- Body weight at weaning: by 5 to 9 pounds

- Average daily gain: by ¼ pound

Becoming established on solid feeds before weaning is important for stimulating rumen function, and better early-life growth translates to earlier onset of puberty and higher milk production at maturity.

Benefits for consumer acceptance. In a Minnesota study, the researchers surveyed over 1300 adults attending the Minnesota State Fair. They were shown photos of calves in single, pair, or small-group pens in a barn. Nearly half of the participants disapproved of individual housing, whereas only 14% of people disagreed with pair housing and only 7% disagreed with group housing. In contrast, two thirds of participants agreed with pair housing and three quarters agreed with group pens, whereas only a third thought single housing was acceptable. Nearly all of these fair-goers consumed dairy products. This is the first study showing that social housing may be important for continued consumer acceptance of dairy production.

Managing calf health. Dairy producers who have chosen to shift to social calf raising have found that changing their management sometimes comes with bumps along the way. Nonetheless, many of the principles for promoting good health outcomes are similar whether managing individuals, pairs, or groups. Limiting the spread of disease between different pairs or groups is still a best practice. The risk of respiratory disease is reduced by feeding sufficient high-quality colostrum to promote passive transfer of immunity, feeding sufficient milk or milk replacer for a high plane of nutrition, and ensuring ventilation for good air quality. Sufficient space, clean and dry bedding, good biosecurity and sanitation, limiting age differences within groups, and all-in-all-out practices are also important.

Minimizing cross sucking. One of the concerns some producers have about pair or group housing is the opportunity for calves to engage in unwanted behaviors like cross sucking. Excessive cross sucking is thought to lead to frostbitten ears, navel infections, or mastitis or udder damage. Although the little research that has been done has not found a consistent relationship between cross sucking and those negative outcomes, there are nonetheless ways to reduce this nuisance behavior.

When calves begin a milk meal, their instinctive suckling behavior is stimulated and continues for at least 20 minutes. Feeding milk or replacer through a teat instead of an open bucket, especially using a slow-flow nipple, can redirect their suckling instinct more appropriately, both while the calf is drinking and afterward.

Last summer, Ms. Salter tested this concept for pair-housed calves in hutches. Calves were bottle fed until they were 2 weeks old, when they were switched to either open buckets or slow-flow teat buckets. All calves were fed 4 quarts of pasteurized milk per meal twice daily. Step-down weaning occurred over the course of 12 days by halving the milk volume at each meal, then feeding only once daily. Calves were totally weaned by 8 weeks of age. Twice a week, Salter recorded the calves’ behaviors during and after the milk meal. She found that when calves were fed milk using slow-flow teats, they spent more time drinking their milk and less time sucking on the water buckets, hutches, fence, and – mostly importantly – on each other.

Regardless of pre-weaning housing, cross sucking sometimes increases directly after weaning. Calves who are better established on solid feed are less likely to cross suck, so gradual, step-down weaning based on starter intake can help.

Pair or group housing options. Social housing can be done in many ways, either in a calf barn or outdoors in hutches or super hutches. Last year, we surveyed over 200 Wisconsin dairy producers and custom calf raisers. Nearly 20% of farms allow their pre-weaned heifers full social contact, either in pairs or larger groups. These producers use a variety of housing, demonstrating that there are many options for successful pair or group raising.

Often times people picture “group housing,” to mean large group pens with automatic milk feeders. Indeed, about a third of producers in our sample who group house use auto-feeders. The most common method, however, was housing calves in pairs or groups in a barn and feeding them manually, either with mob feeders or with individual bottles or buckets. Interestingly, one in five producers using pairs or groups house their calves outdoors, either with “super hutches” or by connecting individual hutches (Photo 1). For producers who currently use outdoor hutches, connecting pairs of existing hutches allows them a way to dip their toes into pair housing without a substantial investment in new housing infrastructure or a major change to their management style.

Heat stress in hutches.Calves housed in outdoor hutches are more exposed to environmental extremes compared to those housed in barns. In the summer, calves may experience dehydration, poor welfare, and show reduced appetite, feed intake, and growth. Some types of plastic hutches can create a greenhouse effect, gaining heat from the sun and warming up inside. To prevent this, shade is the best defense. Trees or shade cloth blocking at least 80% of UV light have been shown to reduce the temperature inside the hutch.

Hutches can also be ventilated to increase airflow and heat exchange. Researchers in Washington found that on days when hutches were raised with cinder blocks, calves had lower respiration rates. Although elevating the hutch is a simple solution, some producers have expressed concerns about calf safety. An alternative is to prop open the rear bedding door, install adjustable windows (such as Calf-Tel calf hutch vent covers – SHOP NOW), or use a combination of these methods. When Ms. Reuscher was an undergraduate at Tarleton State University, she compared these methods on large heifer-grower operations in Texas.

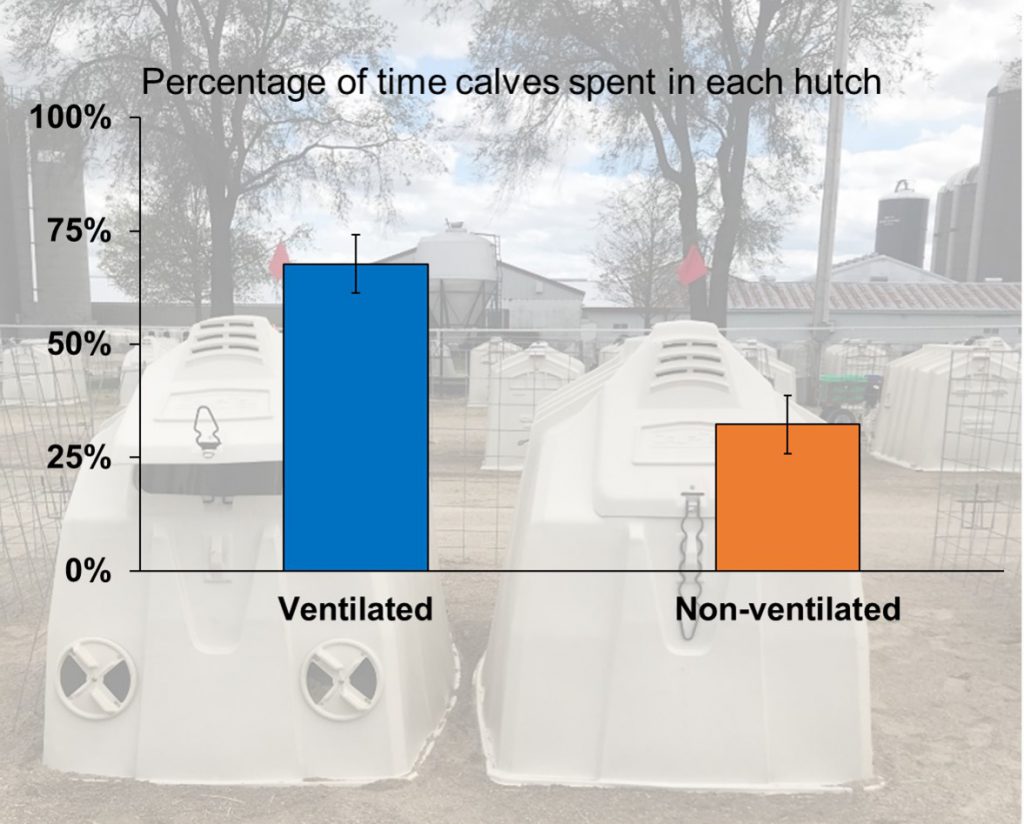

More recently, Reuscher tested 32 pairs of heifer calves in Wisconsin. Each pair was housed in adjacent individual Calf-Tel hutches with a shared fence. Once the calves were paired at around 1 week old, we added ventilation to one of the hutches in each pair by propping open the back bedding door and opening the 2 rear ventilation windows near the base of the hutch.We looked at hutch use in 20 pairs of calves when they were 8 weeks old, right after they were weaned. During the warmest times of day between 12 and 5 pm, we monitored their behavior using time-lapse footage every 5 seconds. Overall, calves spent 68% of their time in the ventilated hutch (Photo 2), with 16 out of the 20 pairs spending over half of their time in that hutch.

On other days during the study, we kept calves inside the hutches for 1 hour of time using a wire fencing panel. They were kept either in separate hutches or in the same hutch together, and we repeated this for both the ventilated and non-ventilated hutch in each pair. Before and after calves were placed inside the hutches, we measured signs of heat stress.

When calves were in the non-ventilated hutch with airflow only through the front door and roof vents, their respiration rates stayed relatively stable over the course of the hour. This indicated that these hutches did not have a greenhouse effect. Calves did not accumulate heat and get hotter over time relative to when they were outdoors – but they did not get cooler either.

In contrast, when calves were in the ventilated hutch, their respiration rates were reduced by 10 to 20 breaths/min over the course of the hour. This demonstrated that hutch ventilation had a cooling effect, helping the calves dissipate heat. These patterns were consistent whether there was only 1 calf in the hutch a time, or both calves in the pair (Photo 3), and whether the calves were in week 4, 6, or 9 of life.

Our initial results are a promising indication that hutch ventilation translates quickly into reduced respiration rates for calves in hutches, even when they are pair housed. Furthermore, the calves seek out hutches with ventilation. By voting with their feet, the calves indicated a significant preference for the cooler environment.

Reuscher is now further analyzing the calves’ behavior along with rectal, skin, and eye temperatures. She also recently finished a winter study to investigate whether pairing in connected hutches may provide an additional benefit for calves, who can help keep each other warm. We will share this information once available. Our goal is to help more dairy producers join the list of success stories for social raising.

Courtesy of our dealer – CRI REPRODUCCIÓN ANIMAL MÉXICO SA DE CV.

Courtesy of our dealer – Holger & Laue Sales GmbH.